PIRE II: Translating cognitive and brain science in the laboratory and field to language learning environments

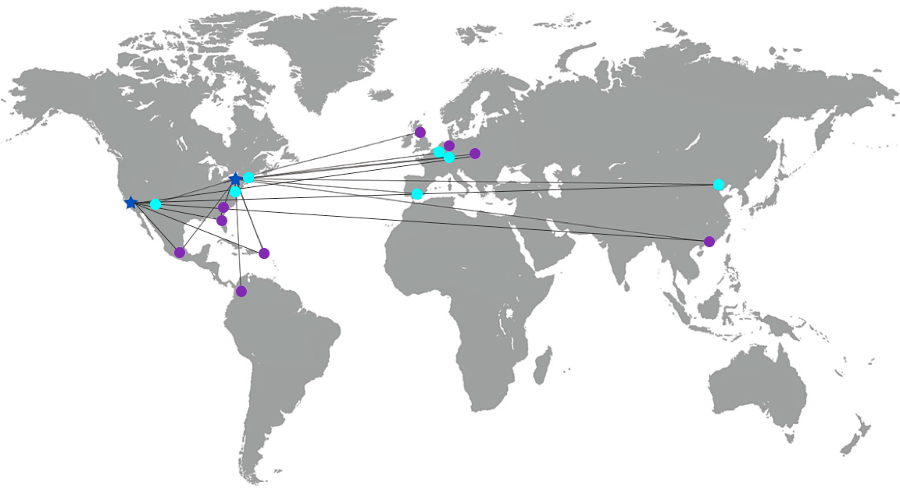

Research Network

Penn State Faculty

- Roger Beaty, Psychology

- Matt Carlson, Spanish and Linguistics

- Amy Crosson, Education

- Michele Diaz, Psychology and Linguistics

- Paola E. Giuli Dussias, Spanish and Linguistics

- Carrie Jackson, German and Linguistics

- Elisabeth Karuza, Psychology

- John Lipski, Spanish and Linguistics

- Carol Miller, Communications Sciences and Disorders

- Karen Miller, Spanish and Linguistics

- Michael T. Putnam, German and Linguistics

- Lisa Reed, French and Linguistics

- Chaleece Sandberg, Communications Sciences and Disorders

- Rena Torres Cacoullos, Spanish and Linguistics

- Janet van Hell, Psychology and Linguistics

- Navin Viswanathan, Communications Sciences and Disorders and Linguistics

UC Irvine Faculty

- Carol Connor, Education

- Richard Futrell, Language Science

- Brandy Gatlin, Education

- Greg Hickok, Cognitive Sciences

- Judith Kroll, Psychology

- Glenn Levine, European Languages and Studies

- Lisa Pearl, Language and Cognitive Science

- Elizabeth Pena, Education

- Gregory Scontras, Language Science

- Julio Torres, Spanish and Portuguese

Domestic Partners

University of Florida

- Jessi Aaron, Spanish and Portuguese

- Edith Kaan, Linguistics

- Jorge Valdes Kroff, Spanish and Portuguese

- Eleonora Rossi, Linguistics

- Stephanie Wulff, Linguistics

Gallaudet University

- Thomas Allen, Educational Neuroscience

- Laura Ann Petitto, Psychology

University of Puerto Rico

- Rosa Guzzardo Tamargo, Hispanic Linguistics

- Luis Ortiz Lopez, Lispanic Linguistics

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Eurydice Bouchereau Bauer, Curriculum and Instruction

University of New Mexico

- Jill Morford, Linguistics

Haskins Laboratories

- Kenneth Pugh, Psychology and Linguistics

International Partners – Latin America

Mexico

- Natalia Arias-Trejo, Psychology at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Colombia

- Marianne Dieck, Languages and Linguistics at the University of Antioquia

International Partners – Europe

The Netherlands

- Dorothee Chwilla, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition, and Behavior at Radboud University Nijmegen

- James McQueen, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition, and Behavior at Radboud University Nijmegen

- Sharon Unsworth, Modern Languages and Cultures at Radboud University Nijmegen

Germany

- Holger Hopp, English Linguistics at University of Braunschweigh

United Kingdom

- Antonella Sorace, Developmental Linguistics at University of Edinburgh

Poland

- Zofia Wodniecka, Psychology at Jagiellonian University

Spain

- Teresa Bajo, Psychology at the University of Granada

International Partners – Asia

CHINA

- Taomei Guo, Psychology at Beijing Normal University

- Hua Shu, Cognitive Neuroscience at Beijing Normal University

- Li Hai Tan, Linguistics and Cognitive Sciences at the University of Hong Kong

- Brendan Weeks, Communication Sciences and Education at the University of Hong Kong

Project Consultants

United States

- Elizabeth Ligon Bjork, Psychology at the UCLA

- Robert Bjork, Psychology at the UCLA

- Susan Goldin-Meadow, Psychology and Human Development at the University of Chicago

- Kimberly Gomez, Education at UCLA

- P. Karen Murphy, Education at Penn State

- Charles Perfetti, Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh

- Joe Salmons, German at the University of Wisconsin

- Naomi Shin, Linguistics and Spanish at the University of New Mexico

- Paula Tallal, Neuroscience at the University of San Diego

Canada

- Ellen Bialystok, Psychology at York University

- Naomi Nagy, Linguistics at the University of Toronto

Mexico

- Rosa María Ortiz Ciscomani, Linguistics at the University of Sonora

Thank you to everyone who works on PIRE II!

Principles for PIRE II

Variation

Within linguistics, there is research on language variation and change. Within cognition, there is research on how variation during early stages of acquisition may enhance basic learning mechanisms. In these two contexts, variation is understood to have different consequences. Language variation is shaped by the social context of language use and informs questions about which aspects of language structure are open to change and which are constrained. In the cognitive context, variation is understood to affect the ability of learners to generalize across input to enhance language development. In the context of L2 learning, these two senses of variation come together because language learners are exposed to a range of input that will vary depending on the circumstances of learning.

Desirable Difficulties

Initial conditions of study that are more difficult, induce errors, and require greater elaborative processing may benefit learning in the long term. Research shows that testing is an important component of learning. Variation itself may introduce a “desirable difficulty” that initially complicates learning but that creates more enduring generalization. An obstacle to the translation of language science to learning environments is that much of the research on language addresses the earliest moments of processing that result incomprehension or plans for speech but fewer studies ask about the long-term consequences of these processes. Research on learning is extended over time and episodes, asking how information is encoded, maintained, and generalized. We bring these lines of research together by using methods for new language learning that will allow us to track both short-term and long-term outcomes.

Implicit vs. Explicit Learning Processes

There is a history of research on implicit vs. explicit language learning and the correlation between learning processes and the age and location of learners. We consider the role of these different methods and contexts and, in particular, consider how neuroscience may reveal the unique contributions of these processes. An exciting discovery is that the brain may outpace behavior in revealing the consequences of initial learning. By bringing neuroscience to learning contexts will we be able to assess the generality of that observation, and only by linking these methods to the timeframe required to assess the stability of new learning, will we be able to fully exploit the convergence across different methods.

The Consequences of Bilingualism and L2 Learning

Much of the excitement about research on bilingualism concerns the potential consequences of bilingualism for enhancing cognition and for tuning brain networks that underlie enhanced cognitive control. The joint activation of the bilingual’s two languages is hypothesized to induce competition. Regulation of competition may be critical to enable proficiency and to produce more general expertise. In what may be the most provocative data on this issue, a group of researchers has shown that lifelong bilingualism appears to protect aging bilinguals against the symptoms of dementia. While some are critical of these claims, there is now evidence on bilinguals of all ages and in different language environments, revealing consequences of bilingualism for behavior and for functional and structural changes in the brain.

Research Themes

Language Learning Across the Lifespan

Research with children: The impact of variable input on language acquisition in children is poorly understood, as most studies assume idealized input with little or no variation. Sociolinguistic variation is pervasive in language input to children; understanding how it impacts language acquisition is vital for a more comprehensive description of language development in monolingual and bilingual children.

Translational implications: By comparing language development in the context of variable input, and focusing on phonological, morphological, and syntactic development in both naturalistic and artificial language learning settings, the goal is to provide foundational data pertaining to the mechanisms involved in language acquisition. These insights not only inform basic science but may also provide a baseline against which language delays may be compared and may suggest more effective routes for pedagogy.

Research with young adults: Many adolescents and young adults must learn an L2 rapidly to enable success in school or work environments. Adolescents are perhaps the most vulnerable language learners. When first immersed in L2, it may be very difficult for learners to prevent themselves from speaking L1. Learning to control the more dominant L1 may impose initial costs to the L1 so that learners are slower to speak the native language and more likely to make errors. However, recent studies suggest that the difficult process of controlling the L1 may eventually benefit the learner. In this sense, immersion learning creates a desirable difficulty. What is not known are the consequences of language immersion as a function of the age and level of the learner, the support within the environment (e.g., whether others use the two languages in the larger community), and the structural similarity across the languages. The cognitive consequences of developing language control may benefit the acquisition of literacy in both languages. However, for immigrant learners, there are also changes to the L1 and a risk of language attrition, with loss of the L1 as L2 learning proceeds.

Translational implications: Results will provide new data on the conditions that encourage or impede acquisition of language and literacy skills. If we identify conditions of learning that produce cognitive benefits to the learner, e.g., by sequencing immersion experiences, the research will suggest designs for immersion environments and information about the role of L1 maintenance in achieving L2 literacy.

Research with older adults: Older adults are the largest growing segment of the US population and it is estimated

that by 2050 older adults will comprise nearly 20% of the total U.S. population. Even healthy older adults experience notable age-related neural and cognitive decline. At the same time, bilingualism appears to confer protections across the lifespan, especially in executive function. Thus, language is an area of cognition with demonstrated plasticity, and one that may buffer against age-related cognitive decline. There is an urgent need to understand how the consequences of bilingualism are experienced across the lifespan and extend to a wider variety of individuals.

Translational implications: A potential impact of this work is that it may identify the source of benefits that may be advantageous in helping older adults maintain independent lifestyles.

The Role of Instructional Approaches for Successful Language Learning

The studies under this theme will address the learning mechanisms that underlie the consequences of different instructional approaches for children and young adults learning a second language. Key questions will be: (1) What are the cognitive bases for optimizing instructional methods for children learning an L2 at school (through foreign language instruction or ESL classes), and how do child-specific, educational, and socio-contextual factors impact L2 learning? (2) To what extent are learning trajectories and factors that help or hinder L2 learning similar or different among classroom based and immersion-based environments? (3) How does L2 instruction impact L1 language and literacy development and L1maintenance? We will exploit the resources and expertise of foreign partners, domestic partners and consultants to establish a unique research network to study school-based L2 learning in different linguistic, educational, and socio-contextual settings.

Translational Implications: By comparing learners who start language instruction at different ages, it will be possible to generate data on the effect of age on the development of language and literacy skills. The outcomes will also serve to refine theoretical models on implicit and explicit learning. Gaining insight into children’s and young adult’s L1 maintenance or loss and L2 development will inform L2 educational practices by providing research-based insights into the effects of second language instruction. These insights will also inform theoretical models on human learning and plasticity, and the dynamic interplay between developing L1 and L2 language systems.

The Role of Diverse Social Environments for Language Learning

Field-based research, especially involving little-studied languages and non-traditional speech communities, can complement laboratory- and corpus-based research, most of which involves a small number of major world languages. By combining field linguistics and laboratory psycholinguistics, new insights into language development, bilingual language processing, and language maintenance are within reach. The inclusion of Latin American partners in the PIRE proposal opens exciting possibilities for training, research, and collaboration involving the intersection of laboratory- and field-based approaches. Many lab techniques can be adapted to differing linguistic ecologies, by creative use of software and portable hardware configurations and by designing experimental protocols not dependent on literacy, metalinguistic training, distraction-proof environments, and the need for multiple repetitions of stimuli.

Translational implications: A broader impact of this research is that it opens many opportunities for engaging underrepresented groups, whose central concerns often include literacy—especially in minority languages and dialects—language revitalization and maintenance, and increasing the awareness of and appreciation for linguistic diversity. Field-based experimental research enhances the possibility for immediate application of results in the places where the greatest needs exist.